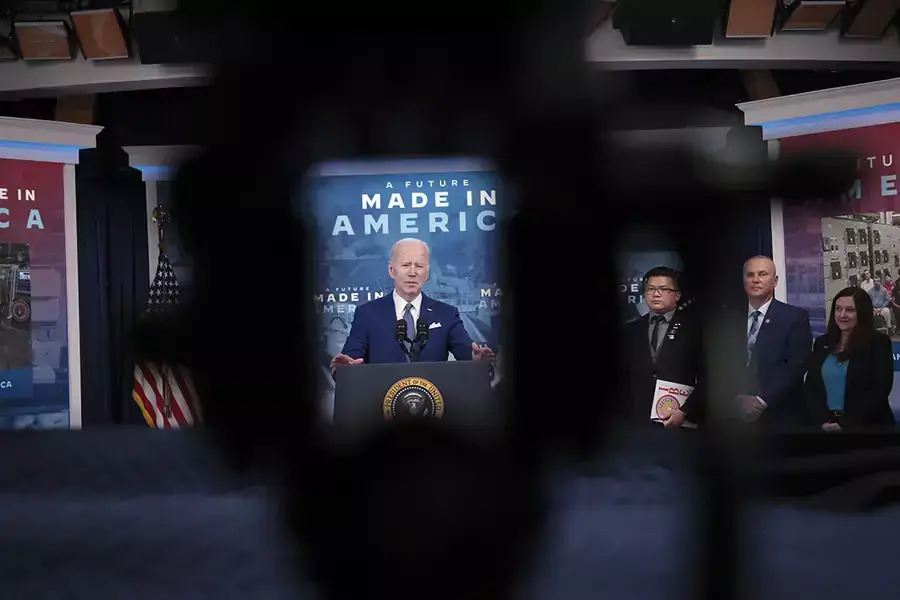

U.S. President Joe Biden’s modern industrial and innovation strategy helped accelerate economic growth in the first half of 2023. As National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan detailed in May, Biden’s economic policies are based on the principles of a “new Washington consensus,” which aims to rebuild the middle class, mitigate climate change, lessen inequality, and strengthen supply-chain resilience. It also lays the foundation for responding economically to the challenge posed by China.

Although the Biden administration’s goals are admirable and worthy, the methods they are using to achieve them, combined with other recent U.S. economic policies, will have high geopolitical costs at a time when the Global South is growing in influence.

Over the past seven years, the United States has paralyzed the dispute settlement system of the World Trade Organization (WTO), levied billions of dollars of tariffs, and declared imports a national security threat. The Biden administration’s approach follows that trend by practicing what Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, calls zero-sum economics, proliferating export controls on computer chips and increasing subsidies and local-content rules.

In response to China’s distortive trade practices, the United States is acting more like China, enacting policies it long criticized others for, and opening itself to retaliation in kind. China is challenging the economic order, but unilateral and ad hoc measures are not as effective as a multilateral approach. Many U.S. policies are angering critical allies and competitors alike, which could complicate collective action against global challenges, impair the U.S. goals of advancing American values and prosperity, and undermine the United States in its geostrategic competition with China.

Industrial policy is nothing new and can be useful, but the Biden administration’s new approach will have geopolitical consequences.

First, those policies could drive the world deeper into a mercantilist dilemma, akin to a security dilemma. As the United States unilaterally increases its economic security, it decreases the economic security of others. The Biden administration can try to reassure allies and competitors it is only responding in kind to China’s nationalist economic policies, but, as Robert Jervis made clear, other states are not so easily reassured, and the perceptions and reactions of other countries, particularly China, are apt to deepen mercantilist policies across the world.

Increased mercantilism at a time of worsening climate change and rising interest rates—and when developing countries are prioritizing economic growth—could potentially fracture the international trading system, force higher costs for consumers, and add more hurdles to innovation.

Second, the U.S. economic-might-makes-right approach is particularly dangerous as the rest of the world is catching up economically, and the United States is trying to enlist partners in action on climate change, pandemic prevention, and its strategic competition with China. Economic tensions could ultimately spill over into separate issue areas, and other countries could be less willing to cooperate on shared challenges, which is already occurring with China.

No matter how benign the Biden administration’s intentions are, perceptions are often more important than reality. It is hard for others not to see the policies as an ambitious attempt to sustain Western predominance. The Global South will also not soon forget the West’s wave of COVID-19 restrictions, hoarding of vaccines, and curbing of the transfer of medical technology.

As the international system is already losing legitimacy in the eyes of the rest of the world, economically shutting out the Global South with trade barriers and domestic investment incentives could either further push those countries toward China or incentivize them to hedge against both great powers to preserve their strategic ambiguity. The U.S. priority of safeguarding technology in supply chains will force countries and businesses to choose between the United States and China, something many are loath to do given both powers’ economic importance.

The twenty-two countries voicing interest in joining the BRICS, including six new official members, should be a warning to those in the West that a growing number of countries are frustrated with a world order that does not reflect their needs and interests.

Third, those policies are part of a larger U.S. trend prioritizing bilateral ties and small pacts over multilateralism, and ad hoc security arrangements over comprehensive economic frameworks. That trend is particularly evident in the Indo-Pacific, where the United States is focusing efforts on promoting the Quad, AUKUS, and other small groupings.

Biden’s decision to skip the East Asia Summit and U.S.-ASEAN Summit in Indonesia last month to sign a new partnership with Vietnam sends mixed signals about U.S. regional commitments. The president’s absence unnecessarily rankled vital U.S. trading partners in the region that are only growing in importance with increasing U.S.-China strategic competition and U.S. de-risking from China.

Three issues arise with that small-pact security approach: even if not intended, the arrangements appear targeted at containing China; they are fragmented; and they lack a substantive economic dimension. The latter is a critical gap because many countries in the Global South are prioritizing economic growth and will look beyond the United States for partnerships.

Narrow executive agreements such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity will struggle to meet the Biden administration’s worthy goals, can be overturned by another administration, and frustrate the developing economies that want U.S. market access. Historically, the United States could enact its preferred rules and enforce obligations through trade agreements that open markets to exports. The new approach loses its leverage to influence new rules and standards because of U.S. unwillingness to give negotiating partners access to the U.S. market.

Although renewing America is important, how it is done matters. The United States cannot be secure or prosperous alone and in hostile political and economic environments. It will need to put forward a much more positive and constructive view of the economic order it wants to see—a sufficient alternative for others to follow instead of one into which they are coerced. As George Kennan recommended in a 1953 task force on containment, U.S. efforts should not be openly related to winning a competition with China but should be addressed to the basic, long-term problems that China’s unfair trade practices present. That is something the United States cannot do alone or only with a few like-minded countries.

First steps could include the Biden administration correcting the discriminatory aspects of recent legislation and working multilaterally to amend the current trade law regime to force China in line with the original “liberal understanding” of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the World Trade Organization.

In the past, the United States restrained its own exercise of power to make its leadership acceptable to other states. Over the past seven years, the United States has demonstrated its willingness to exercise more power and economic coercion to ensure domestic growth irrespective of the international repercussions. If not reconsidered, that approach could increase tensions, lessen U.S. influence in setting global rules, and make the U.S.-led order even more contested. If the United States wants to continue down that path, policymakers should at least be upfront about the costs alienating others will incur.

Source : CFR