The first-ever participation of the leaders of Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand in a NATO summit in late June has fueled speculation that the transatlantic military alliance is seeking to expand into the Indo-Pacific region, with the West aiming to strengthen regional security partnerships to counter Russia, China and North Korea.

In particular, Pyongyang and Beijing have warned about what they see as NATO’s attempt to extend its geographical scope and assert military supremacy in Asia — North Korea has threatened to further bolster its defenses and China has said that such an expansion could lead to turmoil and conflict.

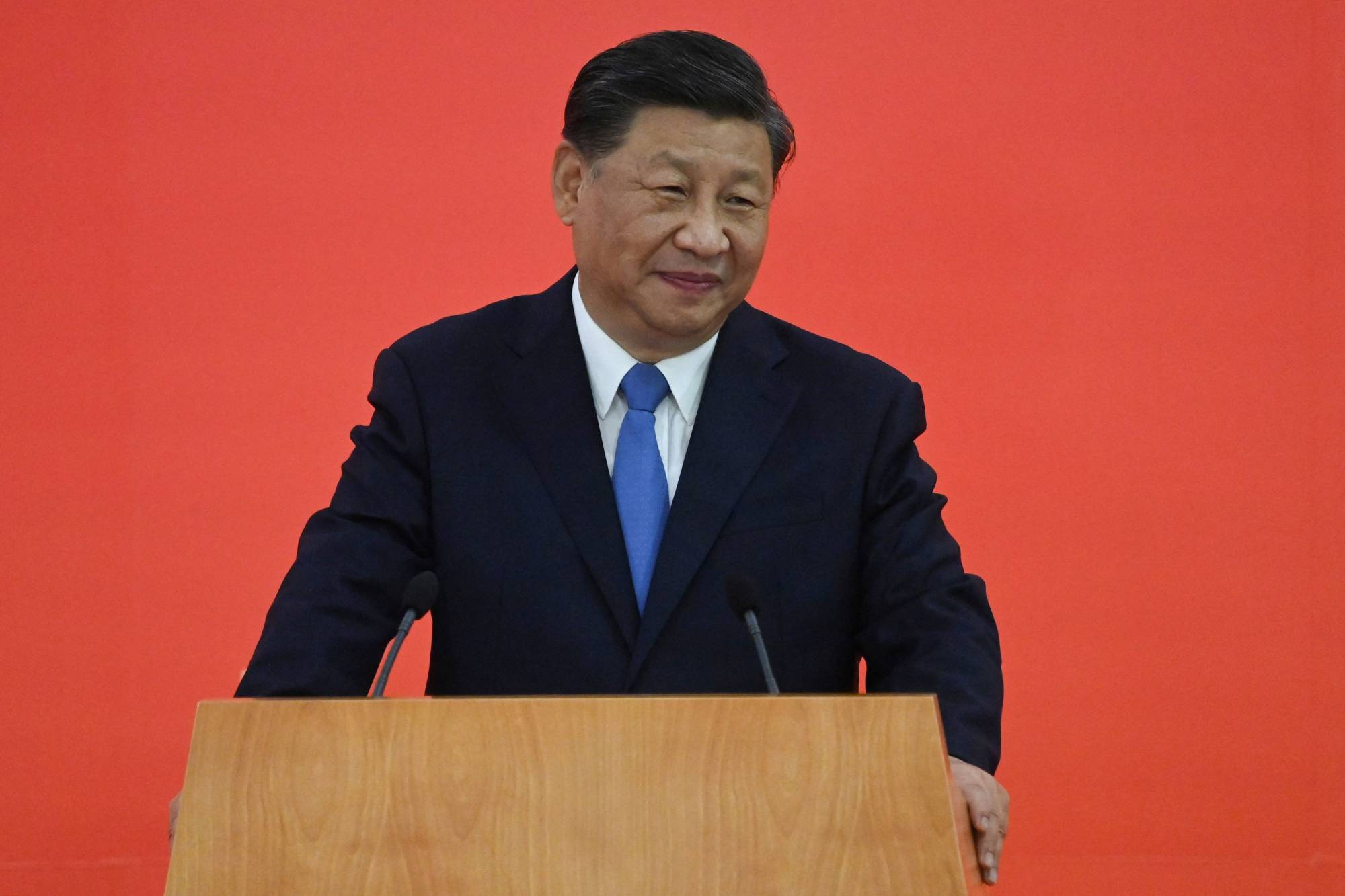

A few days before the NATO meeting in Madrid, Chinese President Xi Jinping warned during a virtual summit of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — known as BRICS — that some nations were attempting to “expand military alliances to seek absolute security, stoke bloc-based confrontation by coercing other countries into picking sides and pursuing unilateral dominance at the expense of others’ rights and interests.”

“If such dangerous trends are allowed to continue, the world will witness even more turbulence and insecurity,” Xi said.

NATO’s view of China

But are the warnings about an Asian expansion justified? The latest NATO summit saw the alliance endorse for the first time a strategic concept addressing the challenges posed by China to NATO’s “interests, security and values,” including Beijing’s growing partnership with Russia and its increased influence in Africa.

“China is substantially building up its military forces, including nuclear weapons, bullying its neighbors and threatening Taiwan. (It is) investing heavily in critical infrastructure, including in allied countries, monitoring and controlling its own citizens through advanced technology and spreading Russian lies and disinformation. … China is not our adversary, but we must be clear-eyed about the serious challenges it represents,” NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg said while presenting NATO’s new doctrine, which calls for a fundamental shift in the alliance’s deterrence and defense posture.

But perhaps more importantly, Stoltenberg said the alliance will step up cooperation with four of its Indo-Pacific partners — Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, which are informally known as the Asia-Pacific Four, or AP4 — in areas such as cyberdefense, new technologies, maritime security, climate change and countering disinformation, arguing that “global challenges demand global solutions.”

Individual NATO member states such as France, Germany and Britain have been deepening bilateral security ties with these four countries in recent years as they adjust their foreign and defense policies to the shifting power structures in the region. However, the latest NATO summit marked the first time the alliance took such a public and firm stance regarding China-related challenges through proposed closer cooperation with regional partners.

‘Like-minded’ countries

NATO argues that it must work closely together with “like-minded countries” in an era of strategic competition where “the core principles of international security” are contested. This means the alliance recognizes the need for closer international coordination in a rapidly changing security environment where China is playing a greater role.

But why these four countries? Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand have been formal NATO partners since the early 2010s, part of a group of “partners across the globe.” These four countries are seen by the alliance as an increasingly important subset of its global partners and were invited to Madrid as part of broader efforts to integrate them into NATO’s structures and functions, according to Mirna Galic, a senior policy analyst for China and East Asia at the United States Institute of Peace.

This is in part due to the character of the partners themselves, Galic said. All these countries are established democracies that share values with NATO member states, are interested in mitigating international security threats and have sophisticated and capable militaries, Galic wrote in an email. Moreover, Australia, Japan and South Korea are also U.S. treaty allies, while New Zealand is a close U.S. partner.

Another important reason is that NATO can greatly benefit from increased interoperability, coordination and information sharing with these countries.

“The Asia-Pacific partner countries have a long history of living with China, balancing economic and security imperatives, pushing back on violations of international law, deterring and dealing with coercive measures, all of which is an immensely valuable insight for European partners,” she noted. “They also sit in a dynamic region of the world, the Indo-Pacific, which is of growing interest to Europe, meaning that their intelligence and analysis regarding what is happening in the region is likewise of great interest.”

Finally, with a strategic competitor located in each region, the re-emergence of great power competition and an evolving China-Russia relationship, Galic argued that both NATO and its partners can benefit from greater interaction on how to adapt to the common strategic challenges they face.

These include managing intermediate-range nuclear forces (INF) in the wake of the collapse of the INF treaty between the United States and Russia, missile defense and extended deterrence, as well as how to push back on the use of force by great powers in contravention of international norms.

“The last is certainly relevant to the Russian invasion of Ukraine but also has parallels with China and Taiwan, which is why Ukraine is seen as more than a European security issue,” Galic noted.

In line with this view, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida stressed the need for more regional security cooperation in his June 10 speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue security forum in Singapore, amid concerns that a crisis similar to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could erupt in Asia.

Many of NATO’s reasons for seeking increased cooperation are also shared by these four countries, said Joseph Liow, a professor and research adviser at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore.

“There is a convergence of interests between the four Indo-Pacific powers and NATO in terms of shared concerns that the international rules-based order is coming under increased strain. Their presence at the recently concluded NATO summit is an expression that they are prepared to work with partners who share similar concerns.”

At the same time, some argue the move could also help these countries — all of which have their own reasons for wanting closer ties with NATO — enhance their deterrence posture in relation to China, Russia and North Korea, although it is unclear what role NATO would play should a conflict break out in the region.

Closer ties, but no ‘Asian NATO’

The White House and the Pentagon have in the past repeatedly rejected Chinese claims that the U.S. is trying to create an Asian version of NATO. While the decisions announced in Madrid certainly indicate an alignment of defense and security interests on global issues between the AP4 countries and NATO, a formal expansion of the alliance into the Pacific looks unlikely.

That’s primarily because these countries already have alliances with the U.S., the country that underpins NATO, making formal accession to the transatlantic alliance somewhat redundant.

“While they probably would not refuse an overture to join NATO to create an Asian version of the alliance, it is not clear that they would benefit much from it, since they already are allied with the U.S.,” said Rafiq Dossani, director of the Center for Asia Pacific Policy at the U.S.-based Rand Corp.

Furthermore, Galic noted that NATO has no interest in making these countries members and that there is also currently no way to do so.

“NATO’s charter specifies that new members may be nominated from Europe and its collective defense clause applies only to attacks on Europe and North America, making it an inappropriate vehicle for the Asia-Pacific region,” she said.

Moreover, a decision by these four countries to join NATO would certainly upset Beijing, which could retaliate both politically and economically. That could take the form of increased military activities, economic coercion and refusing to cooperate on matters related to North Korea.

By relying on separate alliances rather than being integrated into NATO, the risk of the AP4 upsetting Beijing is probably somewhat lower.

Also casting a shadow over the AP4’s formal involvement is the fact that such a defense alliance would be less capable without the support, and possibly even participation, of South and Southeast Asian countries — most, if not all, of which are unlikely to join such a grouping or even create a similar one unless faced with a major disruptive event.

“Asia has always been somewhat averse to alliances, and even more so after the end of the Cold War,” Liow said. “While security cooperation among regional states, as well as between these and external partners, remains a mainstay of the security architecture, this is very different from alliances that entail explicit defense commitments.”

Muddying the debate around the nature of NATO-Asia cooperation is what exactly the “Asian NATO” term actually means.

“I think when people hear the term ‘Asian NATO,’ some may misunderstand that this refers to the expansion of the NATO alliance into Asia,” Galic said. “In fact, that is not on the table, so what ‘Asian NATO’ may refer to, rather, is the creation of a defensive alliance in Asia akin to what NATO is for Europe and North America. Historically, something like that has proven very difficult, as the experiment of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization showed.”

India, for example, would probably look favorably upon an alliance that challenged Chinese hegemony in South Asia and the Indian Ocean, but it would shy away from such a grouping and continue to pursue a position of “strategic neutrality,” New Delhi-based defense analyst Rahul Bedi said.

Domestic political sensitivities also stand in the way

“For India, joining an ‘Asian NATO’ in which it plays second fiddle to the U.S. or other NATO members would be politically unacceptable at home,” Rand Corp’s Dossani said. “There would have to be some major disruptive event (say, a Chinese invasion of India that the country is unable to respond to effectively) to persuade India to join — just as it took the Ukraine war to persuade Sweden and Finland to join NATO.”

As for other parts of Asia, Dossani points out that many countries in this region, especially in Southeast Asia, do not see China as an existential threat and would not want to risk upsetting their largest investor and trading partner by joining or supporting such a grouping.

A warning to Beijing

The Madrid summit, which saw the transatlantic alliance take a hard-line stance on China and its partnership with Russia, marks a significant step both in terms of rhetoric and NATO’s willingness to defend the values, interests and security it sees as being challenged by Beijing on an increasingly global scale. Additionally, the presence of its Indo-Pacific partners at the summit sent out a message of unity between members of the alliance and like-minded countries.

In this regard, NATO’s new doctrine is aimed at laying the groundwork for deeper cooperation, rather than introducing U.S. treaty allies in Asia as full members of the alliance. Furthermore, the NATO summit provided these four countries with a new platform to come together and promote closer coordination and communication.

If NATO’s intention was to send a warning to Beijing that it will defend its interests regardless of the alliance’s traditional geographic scope, then it seems to have succeeded.

While NATO is highly unlikely to expand into Asia, it recognizes that what happens in the region and what Asian countries do can have an impact on it. What the war in Ukraine shows is that security threats in one region can have knock-on effects in others, and this means that coordinating together on defense issues is important, Galic said.

“Just as NATO’s partners in the Asia-Pacific are standing together with Ukraine and providing assistance in the face of Russian aggression — without being in Europe — so could European partners stand together with an Asia-Pacific country in the face of a potential Chinese aggression and provide various forms of assistance,” she said. “It’s about coordination.”

Source : Japan Times