A writer, dancer, playwright, mountaineer and a national tennis champion, Leela Row – the first Indian woman to win a tennis match at the Wimbledon – was as prolific as they come.

In his 1966 book My Contemporaries, art critic Govindraj Venkatachalam recalls meeting Row as a young girl.

“Timid and nervous, she was shy of strangers,” he wrote. “Little did we realise then that this slip of a girl, would at an early age, become an all-India figure and one of the world’s champion tennis players.”

Born in December 1911, Leela Row was the daughter of Raghavendra Row, a renowned physician, and Pandita Kshama Row, one of the foremost Sanskrit scholars of her time.

Row was raised in India and educated at home by her mother. The family would go on to travel in England and France, where Row also studied the arts.

She began learning classical Indian dance at the age of three to improve her physical strength after a bout of malaria.

Venkatachalam met Row through mutual friends of their family and described her as “very versatile”. As a young girl, she was trained in violin by a master in Paris and had a passion for the stage.

It was from her mother that Row inherited her love for tennis.

European sports had gained popularity among Indian women as part of a broader movement for emancipation, Boria Majumdar and JA Mangan write in their book Sport in South Asian Society.

In the 1920s, Kshama Row was among the first few women tennis players in the country – she won the singles title at the Bombay Presidency Hard Court Championships in 1927.

Row soon followed in her mother’s footsteps, dominating the tennis circuit in the country as a singles player while also playing doubles matches with her mother.

In 1931, she won her first title at the All India Championship. She went on to win six more in the following years.

Through the 1920s and 1930s, Row frequently made news for winning matches at championships across the country.

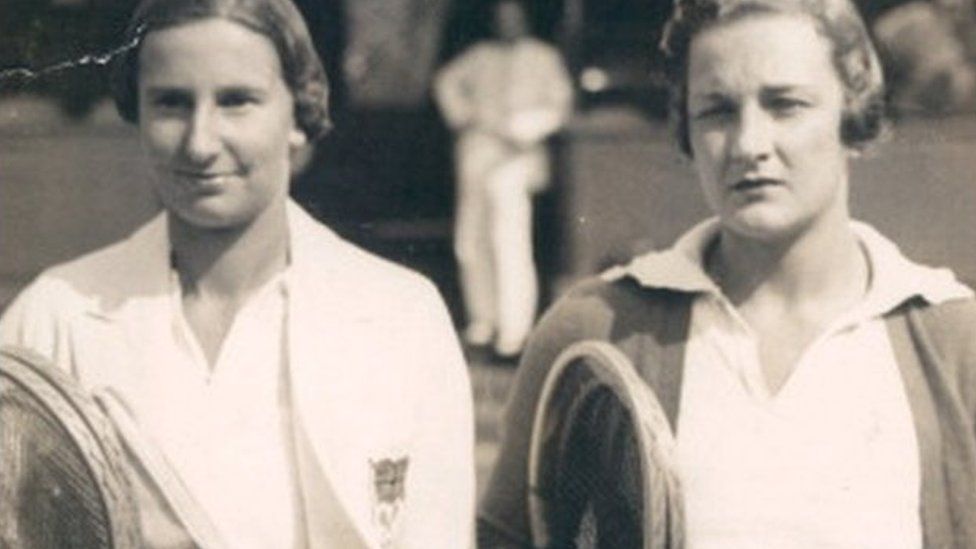

In 1934, she became the first Indian woman to win a match at the hallowed grounds of Wimbledon with a 4-6, 10-8, 6-2 victory over Gladys Southwell of Britain. She lost to France’s Ida Adamoff in the next round.

Row was back at the tournament the next year but lost in straight sets to Britain’s Evelyn Dearman in the first round.

It would be 71 years before another Indian woman – Sania Mirza – would compete in the senior ladies’ draw at the Wimbledon.

“She lived the kind of elite Indian life that could have only taken place in the years between the two World Wars, when the highest echelons of Indian society could simultaneously keep one foot firmly planted in the country of their birth, but another just as firmly, in the broader international networks of the British empire,” writer Sidin Vadukut wrote of her in 2018.

In 1943 , Row married Harishwar Dayal, a civil servant who had represented India at the UN and was then the deputy at India’s embassy in Washington DC.

Row continued to play exhibition tennis matches during her time in the US.

But by the late 1940s, she had turned to her other love – writing about and documenting art.

From her mother, who was considered a pioneer of modernism in Sanskrit, Row had also inherited her love for the language. She adapted several Sanskrit poems written by her mother for the stage.

While she was not a professional dancer, she wrote several books in English and Sanskrit on Indian classical dances.

Her book Natya Chandrika delved into the art of Indian dance and drama, while another one, titled Nritta Manjari delved into the dance sequences of Bharatanatyam.

Natya Chandrika was the first book by an Indian author to be archived by the US Library of Congress, the LA Times reported in 1958.

She also wrote a book on the origins and techniques of the Manipuri dance form, which one reviewer called “a charming introduction” to a “rich and varied treasure of classical Indian dance”.

By the late 1950s, she had spent 20 years researching Indian dance forms and written five books on them. For some of these, she’d posed for the illustrations to demonstrate the form and movement.

“I want to bring out in drawings what my ancestors did in sculpture in the temples of Southeast Asia,” she told the Windsor Daily Star.

In 1963, Row published a children’s book she wrote by hand and bound herself. The book told the story of the mystic poet Meerabai and was based on a Sanskrit poem written by her mother. Row illustrated the story with delicate line drawings in black.

A senior librarian at Singapore’s National Library called it “one of the most treasured possessions in the Asian Children’s Literature collection”, which has some of the oldest and rarest children’s books from Asia.

Row and her husband were “passionately fond of the high mountains,” she wrote in volume 26 of the Himalayan journal. So the couple were happy when Dayal was posted as India’s ambassador to Nepal in 1963.

During her time there, she’d write about the country’s art and architecture.

Row would often go on treks to the mountains, sometimes with her husband or alone.

“It was always some political crisis which prevented us making the trips or returning earlier than expected,” she wrote.

On a trek in the Khumbu region of Mount Everest, Row writes of visiting the Thyangboche monastery – “the first visit of an Indian woman” – and the pleasure of seeing Mount Everest every day.

She called trekking up the Taboche ridge “the biggest thrill of my life”.

“My life’s dream has been fulfilled,” she wrote in the journal.

Dayal died in 1964 while the couple was on another trip to the Khumbu region.

There is little information on how and where Row spent her last years and on her surviving family members.

She was last mentioned The Times of India in 1975 when a bird sanctuary in France exhibited her paintings on Himalayan fauna.

Despite her extraordinary accomplishment, there is little research on Row’s life, making her far from a household name in India.

Source: BBC